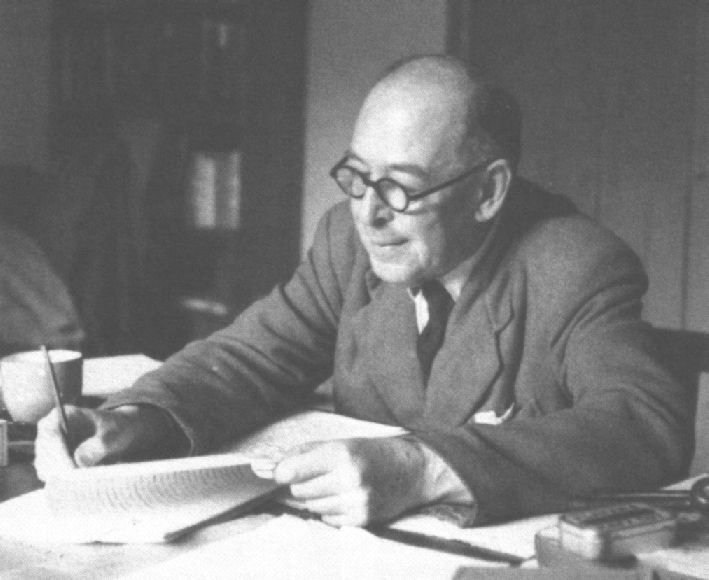

In preparation for my seminar on "Chivalry" I am rereading some key articles and book chapters to see how suitable they are for classroom use. One of these articles is the classic (book publication: 1936) essay "Courtly Love" by C.S. Lewis, author of Narnia, other fantasies, and a lot of Christian polemic originally intended for a popular British audience. (Material on Lewis' writings is all over the Web).

In preparation for my seminar on "Chivalry" I am rereading some key articles and book chapters to see how suitable they are for classroom use. One of these articles is the classic (book publication: 1936) essay "Courtly Love" by C.S. Lewis, author of Narnia, other fantasies, and a lot of Christian polemic originally intended for a popular British audience. (Material on Lewis' writings is all over the Web).The "Courtly Love" essay is at least 70 years old this year, but it's still useful, I think, when supplemented by other more recent discussions. It is, for one thing, amazingly free of academic jargon. There are passages that take the breath away. For instance, I quoted this one for years in a course I used to teach:

It seems to us natural that love should be the commonest theme of serious imaginative literature: but a glance at classical antiquity or at the Dark Ages at once shows us that what we took for 'nature' is really a special state of affairs, which will probably have an end, and which certainly had a beginning in eleventh-century Provence. It seems -- or it seemed to us till lately -- a natural thing that love (under certain conditions) shoud be regarded as a noble and ennobling passion: it is only if we imagine ourselves trying to explain this doctrine to Aristotle, Virgil, St. Paul, or the author of Beowulf, that we become how far from natural it is.Note the complete lack of jargon here. Also (hey, I'm a historian) how his ideas are grounded not in high-flown theoretical assertions, but in historical examples. If you want to argue with Lewis, you know where to begin. And he shows what can be done with ordinary, everyday words.

It seems to me that not too many scholars today want to be as clear and forthright as Lewis was here. But I'm not nostalgic; I think this kind of writing has always been rare.

I am actually pretty far down the ranks of admirers of Lewis's fiction -- there are now millions of adults who fell in love with Narnia as kids, not to mention the kids who are reading about Narnia now -- but I do appreciate the fact that he had a cosmic vision. I grew up a science fiction fan, before it was commonplace, and there is something that Lewis has that a lot of people lack. Look at that quote again and note this:

a special state of affairs, which will probably have an endAh, yes, Clive, you got that right.

Gordon Morrell wrote:

ReplyDeleteSome nice reflections. A couple of years ago when I was researching in Kew, London, I picked up the volume of Tolkien's letters and read them as a distraction. Of course Tolkien and Lewis were close friends and there were many elegant accounts of beer fests at the 'Bird and Baby' pub (better known as the Eagle and Child in Oxford) between the two. The letters they exchanged were equally beautiful and simply powerful and though these two might well have been among the giants of their day or any day, there was a sense refected in these letters that among civil society more widely considered, a level of literacy existed that was rooted in classical education and a mastery of biblical and other shared sources. This is one of the reasons why I am always drawn back to the interwar period 1919-1939 as it is there that one could still see the echos of the 19th century, battered as there were by total war and the emergence of a savage ideological age. For me the world of the Orc, Elf, Dwarf, Wizard, Hobbit and Man is very closely rooted in this broken world, despite Tolkien's protestations

to the contrary. His fantasy world was a reflection of his real world and not an escape.

Sounds like a fascinating course. I don't see why romantic love has to come to an end, though. If you read Lewis's "Four Loves," he seems to think that the ennobling elements of romantic love, when supplemented by Christian charity, elevate the human being beyond a merely "natural" state.

ReplyDelete