A cool, detailed article on the naming of America. Thanks to Boston.com and Explorator for this one.

The expanding horizons began with Vespucci. In his letter, he reported sailing west across the Atlantic, like Columbus. After making landfall, however, he had turned south, in an attempt to sail under China and into the Indian Ocean — and had ended up following a coastline that took him thousands of miles almost due south, well below the equator, into a region of the globe where most European geographers assumed there could only be ocean.

When Ringmann read this news, he was thrilled. As a good classicist, he knew that the poet Virgil had prophesied the existence of a vast southern land across the ocean to the west, destined to be ruled by Rome. And he drew what he felt was the obvious conclusion: Vespucci had reached this legendary place. He had discovered the fourth part of the world. At last, Europe’s Christians, the heirs of ancient Rome, could begin their long-prophesied imperial expansion to the west.

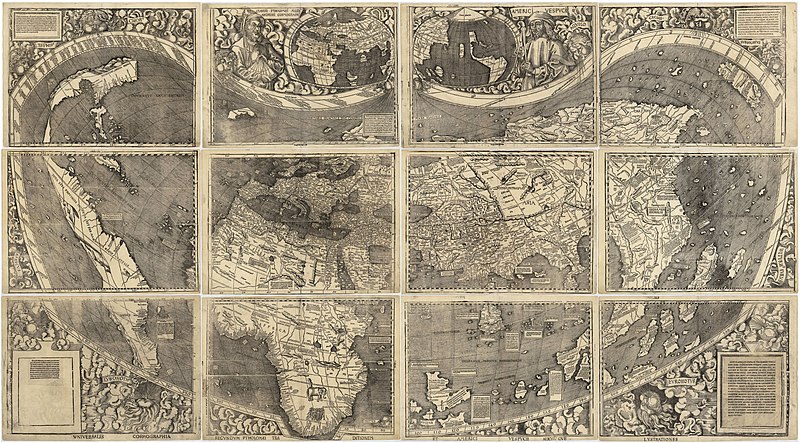

Ringmann may well have been the first European to entertain this idea, and he acted on it quickly. Soon he had teamed up with a local German mapmaker named Martin Waldseemüller, and the two men printed 1,000 copies of a giant world map designed to broadcast the news: the famous Waldseemüller map of 1507. One copy of the map still survives, and it’s recognized as one of the most important geographical documents of all time. That’s because it’s the first to depict the New World as surrounded by water; the first to suggest the existence of the Pacific Ocean; the first to portray the world’s continents and oceans roughly as we know them today; and, of course, the first to use a strange new name: America, which Ringmann and Waldseemüller printed in block letters across what today we would call Brazil.

Why America? Ringmann and Waldseemüller explained their choice in a small companion volume to the map, called “Introduction to Cosmography.” “These parts,” they wrote, referring to Europe, Asia, and Africa, “have in fact now been more widely explored, and a fourth part has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci....Since both Asia and Africa received their names from women, I do not see why anyone should rightly prevent this from being called Amerigen — the land of Amerigo, as it were — or America, after its discoverer, Americus."

"Amerigo" seems to have been a pop. Italian version of the Hungarian name "Imre" - i.e. "Henry".

ReplyDelete