Ancient, medieval, Islamic and world history -- comments, resources and discussion.

Sunday, January 02, 2011

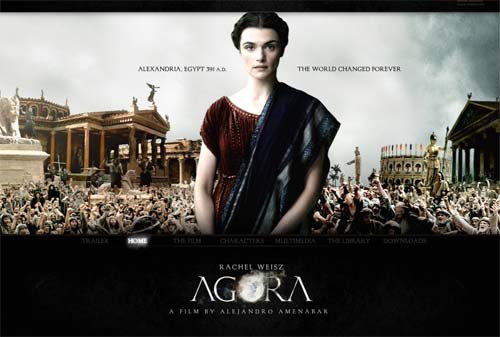

Agora (2009)

This is a seriously good movie.

I haven't heard much unmixed praise for this film, not a lot of commentary at all, and I think it deserves better. So here are my observations.

You should know that the story concerns the 4th century Alexandrian philosopher Hypatia. As a woman philosopher she was an oddity, as an educated pagan she lived in an increasingly hostile environment. Alexandria was a major center for both Christians and pagans, and the two groups were competing for control of the city. The Christians were winning -- they had the support of Theodosius, the eastern emperor who eventually banned pagan observances. The conflict in Alexandria was quite violent at times. This is one of the times that the Library of Alexandria, a pagan institution, is supposed to have been destroyed. More certain is that Hypatia attracted the hostility of the Christian party, and was killed by a mob. It's a depressing story, and one that could easily be butchered.

There are three important aspects to the movie. One is its degree of success in evoking late fourth-century Alexandria. I give Agora very high marks indeed on this. Visually, the evocation of the city, with its mixture of Greek and Egyptian elements, is stunning and flawless. The dialogue likewise does nothing to throw the viewer back into the 21st century, while avoiding pseudo-historical cuteness. That is a harder trick than the mere statement might indicate.

Second is the depiction of the religious conflict between Christians on one hand and Jews and pagans on the other. This is certainly what has made distributors very reluctant to show Agora in most of North America, because the Christians don't come out of it looking good. I, however, have read a lot of late ancient ecclesiastical history, some fair amount of it on the turbulent Alexandrian developments of the era, and I found this account believable. Rioting monks were a staple of Alexandrian religious life, even in purely intra-Christian disputes.

Third is the scientific story. The film proposes that Hypatia came to reject the Ptolemaic view of an earth-centered universe, with the complex series of epicycles to make planetary movements correspond to the predictions of Ptolemy's theory. Instead, says the movie, she became convinced that a more elegant solution was possible, a heliocentric one. Because predictions based on circular orbits won't work, she, like Kepler, comes up with the notion that planets moved on elliptical orbits.

I don't think that there is any evidence that Hypatia did any of this, but that doesn't bother me. But I was sure before I saw Agora that the filmmakers would do a terrible job of this part of the film.

They didn't. Indeed, that part of the plot works very well indeed. Hats off to them. And particularly to the bright guy or gal who suggested intercutting images of the Earth from space in a few appropriate places.

This is a serious, good movie.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

I am pleased to read that you have seen the movie and it did not disappoint you. I will have to try and see it sometime.

ReplyDeleteA very thoughtful review. I saw Agora when it first came out in NYC and loved Weisz' performance as Hypatia. The film was beautifully shot and a bit uneven. Amenabar distorted some history in service to his art (the Library didn't end that way and Synesius wasn't a jerk), but that's what artists do. I go to the movies for entertainment, not history. For people who want to know more about the historical Hypatia, I highly recommend a very readable biography Hypatia of Alexandria by Maria Dzielska (Harvard University Press, 1995). I also have a series of posts on the historical events and characters in the film at my blog - not a movie review, just a "reel vs. real" discussion.

ReplyDeleteI have lately been reading Stephen Mitchell's History of the Later Roman Empire, AD 284-641 (Oxford 2007), which of course covers this as well as other monkish mob violence in Alexandria, and was very struck by this, albeit not in a nice way:

ReplyDeleteThe historical accounts of these episodes in Alexandria leave open many questions about their causes, but they provide a clear sense of their social context and illustrate the brutalization of local politics. The bishops of the city could call on ill-educated supporters from the proletariat, who did not hesitate to employ extreme violence in a fanatical cause. It is revealing that the city councilors of Alexandria, an educated minority, petitioned the emperor in 416 in protest against the violence of the gangs of the bishop's supporters.... Theodosius II responded only as far as ordering that their numbers should be limited in future to five or six hundred persons. (Pp. 320-321)

Five or six hundred persons! How many were they before? And it's not that every bishop was doing this, because Bishop Cyril took a bunch of these guys to the Council of Ephesus in 431 and basically strong-armed the Council into starting Nestorianism (by expelling Bishop Nestor from his see). This wasn't a roots religious movement: this was a fanatical politician and his stormtroopers operating with state cognizance. Bad time to be in Alexandria...