His reflections after fulfilling a life-long dream:

I have my owned preferences about interpreting Knossos, but until now they’ve been based on photographs, written descriptions, and site plans. These second-hand things give little feeling for the three-dimensional reality. It was only after examining every corner of the real site that I could confidentially feel confirmed in my own interpretations. I am convinced that the “palace” of Knossos was no palace. The Minoan state of Knossos may or may not have had kings, but if they did, this complex was not an expression of it. It is nothing like the royal palaces of Mesopotamia.

The most discussed part of the complex is the Central Plaza, which Evans visualized as a palace courtyard, and the venue for the bull-leaping portrayed in Minoan art. The plaza seems singularly impractical for such an activity, but it is not impossible. Whatever ceremonies were performed there, it seems to me unlikely that they were primarily for the entertainment of a king, queen and court. Communal feasting seems more likely. Perhaps the bull-leaping was done elsewhere, and the bull brought to the plaza for sacrifice. Large quantities of cups have been found, to delicate for normal use, and there are other signs of large-scale cooking.

The most important alternative explanation of the primary purpose of the complex has been that it might have been a monastic complex. There are striking analogies in its layout to monastic complexes in Tibet (which also focus on a rectangular plaza), or the medieval European monasteries (which also had extensive storage and workshop facilities). I think this is closer to the truth, but I would take the argument a step further. At one point, I turned to Filip and said: “This is an Agora.”

Everything about the place says “Agora” to me. In my mind’s eye, I can see a market place (gr. agora), springing up between two or small sacred places that have turned into sanctuaries and places of pilgrimage. These gradually evolved into shrines served by priestesses, and eventually into a complex of monastic institutions, but always maintaining the central open space for a mixture of commercial, ritual, judicial, and political use. There is no one overwhelming sacred place, as with a Cathedral or a Mesopotamian temple. There is no one central audience hall where a king could overawe his subjects. The structure which Evans imagined to be a royal throne room is completely inappropriate for such use. It’s a small room, with a small chair set against the longest wall, at floor level. The “throne” faces a narrow space partly filled with some kind of offering bowl. Nobody ever built throne rooms like that. The aesthetics is overwhelmingly intimate and religious, not monarchical. No king who could command the impressive resources of so wealthy a state would be content with such a dinky little room, in which he could impress no one. All over the complex, there are no murals conveying kingly power and authority, nothing saying “look on this, ye mighty, and despair.” There are only pictures of flowers, children playing games, dolphins leaping in the sea, farmers harvesting their crops, athletes, elegant ladies, pets, and so on. The architectural feature are everywhere consistent with domestic, commercial, and small-scale religions uses.

At some points in time, the whole complex seems to have been consolidated or rebuilt by a uniform plan, but that is quite possible in a non-monarchical context. The Agora of Athens underwent such a process under democratic rule.

Which brings us to the intriguing possibility that Knossos, and the other Minoan cities such as Malia, Phaestos, and Gortyn might have been republics of some kind. Of course, no proof exists for such a hypothesis, but no proof exists for Evan’s royalist interpretation, or subsequent priestly theories. The level of evidence simply does not permit any certainties. Only the possibility of deciphering the Linear A or the hieroglyphic texts holds any hope for that. But I think that a republican interpretation has been resisted by archaeologists and historians under the influence of dubious assumptions about linear social evolution.

The emergence of republican state institutions in the 18th and 19th centuries was partly inspired and harked back to Medieval and Renaissance republics, though the continuity between them was slim stuff, and largely dependent on folkloric institutions below the state level. The Medieval republics similarly harked back to the Classical republics of Greece and Rome, though again the continuity was ephemeral. It may be that the Democracy that emerged in the Greek polis of the fourth century BC was itself harking back to remote precedents in the Bronze Age.

Before coming here, I had no clear notion of the broader physical setting of Knossos. The “palace” was surrounded by a large (by Bronze Age standards) city, of which we know very little. There were some large outlying structure, and probably a network of villages subservient to, or integrated with the city. There were roads which led directly to the central plaza — another feature that suggests an Agora. It’s only when you stand in them that you grasp that they were as technically advanced as anything the Romans built. The plaza is aligned with the region’s most dramatic looking mountain peak. It is in a valley of fabulous agricultural potential. The surrounding hills are terraced, and from what I gather the terraces, constantly rebuilt, were there in Minoan times. This valley in turn was part of a system of broad, fertile valleys and plains that dissects the island of Crete, with other major Minoan sites scattered in it. This area is extraordinarily beautiful. The Neolithic agricultural “package” of domestic animals and crops would have supported a very high standard of living, and combined with fishing and sea trade would have made life very sweet by ancient standards. The murals don’t seem to lie.

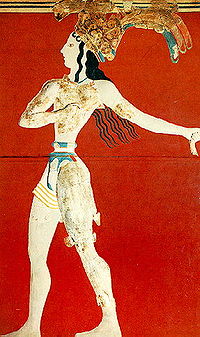

We returned to Iraklion and visited its Archaeological Museum. This was almost as great a pleasure as Knossos itself. It contains most of the famous artifacts unearthed at Knossos. It’s only when you see them in real life that you can fully appreciate them. Some are of great beauty. Some are just delightful, like the toy or model house, which is so detailed and obviously intended to be realistic that we can confidently picture what Minoan houses actually looked like. The famous murals are there. You can imagine my delight at being photographed in front of the “Prince of the Lilies” mural that adorned my website for years.

Image: the mural.

Its a great visit here. It makes my mind to visit here. thanks to share with us.

ReplyDelete