The Guardian tells us what will happen when Queen Elizabeth dies

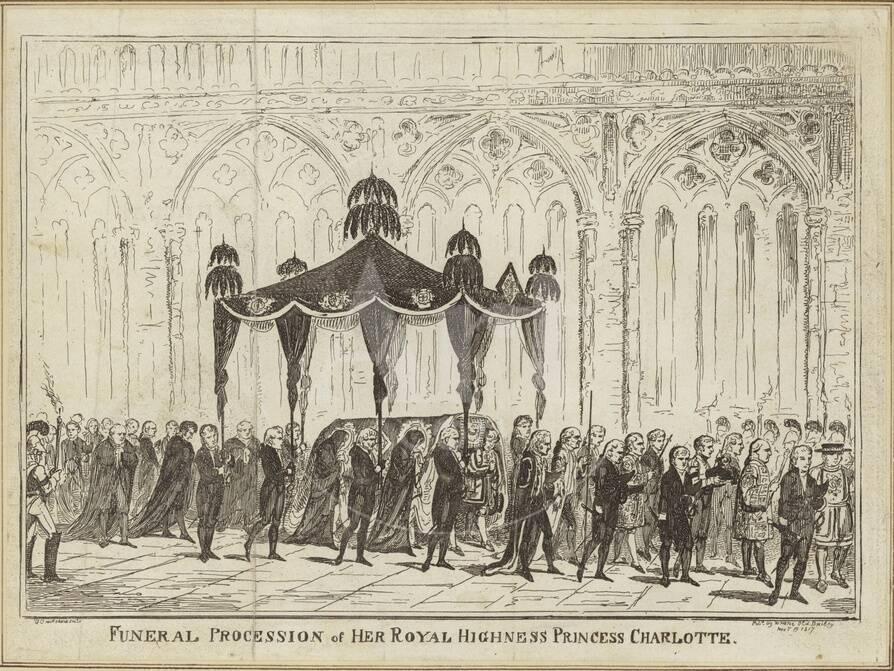

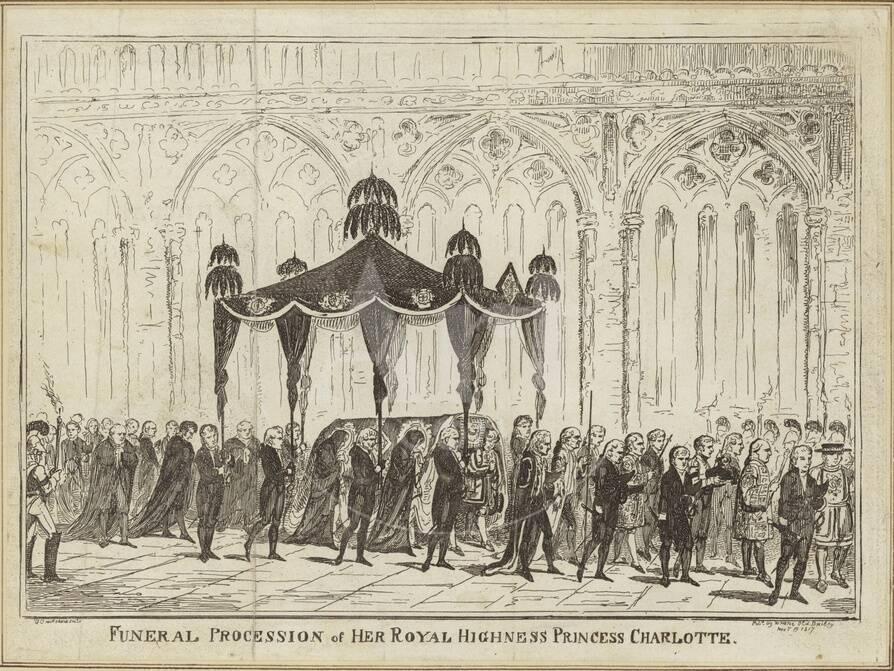

For a long time, the art of royal spectacle was for other, weaker peoples: Italians, Russians, and Habsburgs. British ritual occasions were a mess. At the funeral of Princess Charlotte, in 1817, the undertakers were drunk. Ten years later, St George’s Chapel was so cold during the burial of the Duke of York that George Canning, the foreign secretary, contracted rheumatic fever and the bishop of London died. “We never saw so motley, so rude, so ill-managed a body of persons,” reported the Times on the funeral of George IV, in 1830. Victoria’s coronation a few years later was nothing to write home about. The clergy got lost in the words; the singing was awful; and the royal jewellers made the coronation ring for the wrong finger. “Some nations have a gift for ceremonial,” the Marquess of Salisbury wrote in 1860. “In England the case is exactly the reverse.”

What we think of as the ancient rituals of the monarchy were mainly crafted in the late 19th century, towards the end of Victoria’s reign. Courtiers, politicians and constitutional theorists such as Walter Bagehot worried about the dismal sight of the Empress of India trooping around Windsor in her donkey cart. If the crown was going to give up its executive authority, it would have to inspire loyalty and awe by other means – and theatre was part of the answer. “The more democratic we get,” wrote Bagehot in 1867, “the more we shall get to like state and show.”

Obsessed by death, Victoria planned her own funeral with some style. But it was her son, Edward VII, who is largely responsible for reviving royal display. One courtier praised his “curious power of visualising a pageant”. He turned the state opening of parliament and military drills, like the Trooping of the Colour, into full fancy-dress occasions, and at his own passing, resurrected the medieval ritual of lying in state. Hundreds of thousands of subjects filed past his coffin in Westminster Hall in 1910, granting a new sense of intimacy to the body of the sovereign. By 1932, George V was a national father figure, giving the first royal Christmas speech to the nation – a tradition that persists today – in a radio address written for him by Rudyard Kipling.

The shambles and the remoteness of the 19th-century monarchy were replaced by an idealised family and historic pageantry invented in the 20th. In 1909, Kaiser Wilhelm II boasted about the quality of German martial processions: “The English cannot come up to us in this sort of thing.” Now we all know that no one else quite does it like the British.

The Queen, by all accounts a practical and unsentimental person, understands the theatrical power of the crown. “I have to be seen to be believed,” is said to be one of her catchphrases. And there is no reason to doubt that her funeral rites will evoke a rush of collective feeling. “I think there will be a huge and very genuine outpouring of deep emotion,” said Andrew Roberts, the historian. It will be all about her, and it will really be about us. There will be an urge to stand in the street, to see it with your own eyes, to be part of a multitude. The cumulative effect will be conservative. “I suspect the Queen’s death will intensify patriotic feelings,” one constitutional thinker told me, “and therefore fit the Brexit mood, if you like, and intensify the feeling that there is nothing to learn from foreigners.”

No comments:

Post a Comment